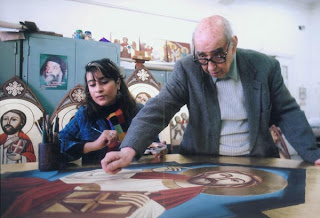

We were in his atelier in the Church of Saint Mark complex in Cairo, and as the master bent to correct a line on an icon being painted by one of his apprentices, to alter the fold of a robe on another, he revealed his deep and profound religiosity.

"An icon in a church signifies the spiritual presence of Christ, the saints and events in their lives," he says. "It is a faithful representation of the Holy Scripture or a biography of a saint. Nothing may be added by way of intervention. An icon painter is not just an artist, but a person who has a deep understanding of church dogma. Christianity holds the human figure as the focus of its visual expression. This is mainly due to its belief in the incarnation of the Logos, the second person of the Holy Trinity, as expressed in the first lines of St John's Gospel: 'and the Word was made flesh'," he adds.

Early life and teaching

Fanous, who resurrected the sacred art of the Copts in the 20th century, was born in Cairo in 1919. As a dynamic and ambitious young man, he entered in the faculty of the applied arts at Cairo University in 1937 and showed an aptitude in a variety of mediums -- painting, sculpture, mosaics and frescoes.

Political changes

Fanous's contemporary school of iconography came about as part of a general renaissance of Coptic culture which began during the patriarchate of Abba Kyrillos VI in the years following the 1952 revolution. As wealthy patrons of the arts disappeared from Egypt's hitherto cosmopolitan art world they were replaced by the state, and the career of Fanous took off from the struggles and experiences of his time. That is to say, he became more keenly aware of his Egyptian heritage.

He noted that in ancient Egyptian art, depictions of important people were always accompanied by their names, and this continued with Coptic icons where these were sometimes in Coptic, sometimes in Arabic, and at other times in both languages. The main figure was also invariably shown larger than the others, whether in Pharaonic paintings and reliefs or in Coptic art. "When I was still a student studying the artefacts in the Egyptian Museum and the Coptic Museum, I recognized strong elements of continuity in Egyptian culture," Fanous said, noting especially that the techniques employed in the painting of icons on wooden panels had changed little over the millennia. These included encaustic on gesso -- which is to say molten beeswax made into an emulsion soluble in water -- developed to a high standard during the early Roman period; this is clear in the beautiful Fayoum portraits, the immediate predecessors of the Christian icon.

Fanous was one of the first students of the Institute of Coptic Studies founded in 1954 and he obtained his doctorate in 1958 . His two-year study grant in the Louvre in the mid- 1960s was a turning point in his career. He took the opportunity, while in France, to study icon painting under Léonid Ouspensky, under whose patronage he developed a passion both as artist and theologian. This would lead, eventually, to his developing a style that was become the new face of Coptic iconography in the mid-20th century.

Fanous posed no such questions. He saw the portrayal of religious figures is part of an ancient Egyptian tradition, and representations of Holy figures as aids to religious understanding. "Icons stand on the threshold between the material and spiritual realms," he says, stressing that the simplicity and the contour of a Coptic icon were reminiscent of hieratic Pharaonic art. "I am convinced of a direct link between ancient Egyptian and Coptic art," he says. "We live in eternity and we have to dig into our heritage."

Fanous's words echo those of Ouspensky who claimed, in one of his many publications, that the Christian image constituted a true confession of the Christian faith. "The orthodox icon opens an immense vision to us which embraces the past and the future in one constant present," he wrote.

Fanous is a modest man, friendly by nature, and a master of preparation, design, gilding and painting. The miracle of his brush strokes and his illumination through color and light are trademarks of his expertise. His is an exceptional union between Pharaonic, early Christian, Byzantine and 18th and 19th-century Coptic imagery. He encourages his apprentices to trace the line of the orbits, place the eyes in position, then the nose and the mouth along these parameters. "Christ and the saints are always represented full face. The profile is reserved for the malicious ones, the soldiers who whip Jesus, and Judas," he adds. "The cross... once a symbol of shame, has become the sign of glory".

Fanous points out that the large dark eyes of the saints are a hallmark of early Coptic art, and notes the progress his apprentices are making in their work. "They stare from beyond the onlooker and reflect poignant sadness, even aloofness. The icons are without human emotions. Each gesture has a precise significance," he says. "Designs should be free of unnecessary elements and decorations. The idea is to present the viewer with the essential information to understand and experience the icon. Colors also carry symbolic meaning."

Turning Point

In 1971 came a second turning point in the career of Fanous. His great fresco in the Cathedral of Saint Mark in Cairo, depicting the martyrdom of the saint, was unveiled. It is a masterly creation. His work, which reflects modern cubist and impressionistic trends, are easily recognizable because he has established basic proportions on which each is based.

The holy figures portrayed in the icons of Fanous, like the ancient pharaoh as a god, are without personality, emotion, or character. They are divorced from human sentiment and passion. The face of Jesus Christ in varied icons of the passion, whether depicted fallen to his knees beneath of the Cross, struggling to mount a hill beneath its weight, or nailed to it, is devoid of pain. Unlike the classical paintings in which Jesus Christ is depicted as Man, suffering as a man, Christ in Coptic art is more frequently depicted triumphant -- reborn, benevolent and righteous.

This is, of course, what the Coptic faithful, whether in Egypt or abroad, wish to see. When they observe icons of the passion of Jesus, they are reminded that His suffering was so that they should be redeemed, but not to feel the pain themselves. Fanous brings them in touch with their deep-rooted faith and their heritage.

Now in his 86th year, Fanous is assured that his legacy will endure. Thanks to his art, simple icon and majestic wall painting alike, Copts feels safe, free from the woes of the world and at peace within the confines of a Coptic Church. They light candles or pray before the icon of a protective saint or the portrayal of a biblical event which is painted in a rigidity of style that is familiar to them.

Apprentices

Fanous's adoring apprentices who strictly adhere to a canon of proportion, and an artistic vocabulary he laid down, uphold the cultural and spiritual Coptic heritage that he set in motion. Nevertheless, in adhering to the stylised and unchanging tradition of the master one cannot help but wonder to what extent Fanous's apprentices -- who include such talented artists as Dalia Sobhi, Armeya Naguib, Aymen Adib and Raif Ramzi -- have become slaves to his image. They, of course, deny this. "We are encouraged to read the bible, chose any passage to portray individuals or subjects that are not in the popular repertoire of Coptic art, even saints, martyrs and holy people more widely known in the West and the Levant than in Egypt," apprentice Emad Bibawi, who chose Rebecca and as subject matter, says. "We are encouraged to innovate."

References

Isaac Fanous

ENTRETIEN AVEC ISAAC FANOUS

PROFESSOR ISAAC FANOUS YOSSEF

No comments:

Post a Comment