The word Copt is derived from the Greek word Aigyptos, which was, in turn, derived from "Hikaptah", one of the names for Memphis, the first capital of Ancient Egypt. The modern use of the term "Coptic" describes Egyptian Christians, as well as the last stage of the ancient Egyptian language script. Also, it describes the distinctive art and architecture that developed as an early expression of the new faith.

The Coptic Church is based on the teachings of Saint Mark who brought Christianity to Egypt during the reign of the Roman emperor Nero in the first century, a dozen of years after the Lord's ascension. He was one of the four evangelists and the one who wrote the oldest canonical gospel. Christianity spread throughout Egypt within half a century of Saint Mark's arrival in Alexandria as is clear from the New Testament writings found in Bahnasa, in Middle Egypt, which date around the year 200 A.D., and a fragment of the Gospel of Saint John, written using the Coptic language, which was found in Upper Egypt and can be dated to the first half of the second century. The Coptic Church, which is now more than nineteen centuries old, was the subject of many prophecies in the Old Testament. Isaiah the prophet, in Chapter 19, Verse 19 says "In that day there will be an altar to the LORD in the midst of the land of Egypt, and a pillar to the LORD at its border."

Although fully integrated into the body of the modern Egyptian nation, the Copts have survived as a strong religious entity who pride themselves on their contribution to the Christian world. The Coptic church regards itself as a strong defendant of Christian faith. The Nicene Creed, which is recited in all churches throughout the world, has been authored by one of its favorite sons, Saint Athanasius, the Pope of Alexandria for 46 years, from 327 A.D. to 373 A.D. This status is well deserved, after all, Egypt was the refuge that the Holy Family sought in its flight from Judea: "When he arose, he took the young Child and His mother by night and departed for Egypt, and was there until the death of Herod, that it might be fulfilled which was spoken by the Lord through the prophet, saying, "Out of Egypt I called My Son" [Mathew 2:12-23].

The contributions of the Coptic Church to Christendom are many. From the beginning, it played a central role in Christian theology---and especially to protect it from the Gnostics heresies. The Coptic Church produced thousands of texts, biblical and theological studies which are important resources for archeology. The Holy Bible was translated to the Coptic language in the second century. Hundreds of scribes used to write copies of the Bible and other liturgical and theological books. Now libraries, museums and universities throughout the world possess hundreds and thousands of Coptic manuscripts.

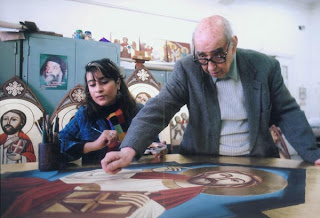

The Catechetical School of Alexandria is the oldest Catechetical School in the world. Soon after its inception around 190 A.D. by the Christian scholar Pantanaeus, the school of Alexandria became the most important institution of religious learning in Christendom. Many prominent bishops from many areas of the world were instructed in that school under scholars such as Athenagoras, Clement, Didymus, and the great Origen, who was considered the father of theology and who was also active in the field of commentary and comparative Biblical studies. Origen wrote over 6,000 commentaries of the Bible in addition to his famous Hexapla. Many scholars such as Saint Jerome visited the school of Alexandria to exchange ideas and to communicate directly with its scholars. The scope of the school of Alexandria was not limited to theological subjects, because science, mathematics and the humanities were also taught there: The question and answer method of commentary began there, and 15 centuries before Braille, wood-carving techniques were in use there by blind scholars to read and write. The Theological college of the Catechetical School of Alexandria was re-established in 1893. Today, it has campuses in Alexandria, Cairo, New Jersey, and Los Angeles, where priests-to-be and other qualified men and women are taught among other subjects Christian theology, history, Coptic language and art---including chanting, music, iconography, tapestry etc.

Monasticism was born in Egypt and was instrumental in the formation of the Coptic Church's character of submission and humbleness, thanks to the teachings and writings of the Great Fathers of Egypt's Deserts. Monasticism started in the last years of the third century and flourished in the fourth century. Saint Anthony, the world's first Christian monk was a Copt from Upper Egypt. Saint Pachom, who established the rules of monasticism, was a Copt. And, Saint Paul, the world's first anchorite is also a Copt. Other famous Coptic desert fathers include Saint Makarios, Saint Moses the Black, and Saint Mina the wondrous. The more contemporary desert fathers include the late Pope Cyril VI and his disciple Bishop Mina Abba Mina. By the end of the fourth century, there were hundreds of monasteries, and thousands of cells and caves scattered throughout the Egyptian hills. Many of these monasteries are still flourishing and have new vocations till this day. All Christian monasticism stems, either directly or indirectly, from the Egyptian example: Saint Basil, organiser of the monastic movement in Asia minor visited Egypt around 357 A.D. and his rule is followed by the eastern Churches; Saint Jerome, who translated the Bible into Latin, came to Egypt around 400 A.D. and left details of his experiences in his letters; Saint Benedict founded monasteries in the sixth century on the model of Saint Pachom, but in a stricter form. And countless pilgrims visited the "Desert Fathers" and emulated their spiritual, disciplined lives. There is even evidence that Copts had missionaries to Nothern Europe. One example is Saint Moritz of the Theban Legion who was drafted from Egypt to serve under the Roman flag and ended up teaching Christianity to inhabitants of the Swiss Alps, where a small town and a Monastery that contains his relics as well as some of his books and belongings are named after him. Another saint from the Theban Legion is Saint Victor, known among Copts as "Boktor".

Under the authority of the Eastern Roman Empire of Constantinople (as opposed to the western empire of Rome), the Patriarchs and Popes of Alexandria played leading roles in Christian theology. They were invited everywhere to speak about the Christian faith. Saint Cyril, Pope of Alexandria, was the head of the Ecumenical Council which was held in Ephesus in the year 430 A.D. It was said that the bishops of the Church of Alexandria did nothing but spend all their time in meetings. This leading role, however, did not fare well when politics started to intermingle with Church affairs. It all started when the Emperor Marcianus interfered with matters of faith in the Church. The response of Saint Dioscorus, the Pope of Alexandria who was later exiled, to this interference was clear: "You have nothing to do with the Church." These political motives became even more apparent in Chalcedon in 451, when the Coptic Church was unfairly accused of following the teachings of Eutyches, who believed in monophysitism. This doctrine maintains that the Lord Jesus Christ has only one nature, the divine, not two natures, the human as well as the divine.

The Coptic Church has never believed in monophysitism the way it was portrayed in the Council of Chalcedon! In that Council, monophysitism meant believing in one nature. Copts believe that the Lord is perfect in His divinity, and He is perfect in His humanity, but His divinity and His humanity were united in one nature called "the nature of the incarnate word", which was reiterated by Saint Cyril of Alexandria. Copts, thus, believe in two natures "human" and "divine" that are united in one "without mingling, without confusion, and without alteration" (from the declaration of faith at the end of the Coptic divine liturgy). These two natures "did not separate for a moment or the twinkling of an eye" (also from the declaration of faith at the end of the Coptic divine liturgy).

The Coptic Church was misunderstood in the 5th century at the Council of Chalcedon. Perhaps the Council understood the Church correctly, but they wanted to exile the Church, to isolate it and to abolish the Egyptian, independent Pope, who maintained that Church and State should be separate. Despite all of this, the Coptic Church has remained very strict and steadfast in its faith. Whether it was a conspiracy from the Western Churches to exile the Coptic Church as a punishment for its refusal to be politically influenced, or whether Pope Dioscurus didn't quite go the extra mile to make the point that Copts are not monophysite, the Coptic Church has always felt a mandate to reconcile "semantic" differences between all Christian Churches. This is aptly expressed by the current 117th successor of Saint Mark, Pope Shenouda III: "To the Coptic Church, faith is more important than anything, and others must know that semantics and terminology are of little importance to us." Throughout this century, the Coptic Church has played an important role in the ecumenical movement. The Coptic Church is one of the founders of the World Council of Churches. It has remained a member of that council since 1948 A.D. The Coptic Church is a member of the all African Council of Churches (AACC) and the Middle East Council of Churches (MECC). The Church plays an important role in the Christian movement by conducting dialogues aiming at resolving the theological differences with the Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Presbyterian, and Evangelical Churches.

Perhaps the greatest glory of the Coptic Church is its Cross. Copts take pride in the persecution they have sustained as early as May 8, 68 A.D., when their Patron Saint Mark was slain on Easter Monday after being dragged from his feet by Roman soldiers all over Alexandria's streets and alleys. The Copts have been persecuted by almost every ruler of Egypt. Their Clergymen have been tortured and exiled even by their Christian brothers after the schism of Chalcedon in 451 A.D. and until the Arab's conquest of Egypt in 641 A.D. To emphasize their pride in their cross, Copts adopted a calendar, called the Calendar of the Martyrs, which begins its era on August 29, 284 A.D., in commemoration of those who died for their faith during the rule of Diocletian the Roman Emperor. This calendar is still in use all over Egypt by farmers to keep track of the various agricultural seasons and in the Coptic Church Lectionary.

For the four centuries that followed the Arab's conquest of Egypt, the Coptic Church generally flourished and Egypt remained basically Christian. This is due to a large extent to the fortunate position that the Copts enjoyed, for the Prophet of Islam, who had an Egyptian wife (the only one of his wives to bear a child), preached especial kindness towards Copts: "When you conquer Egypt, be kind to the Copts for they are your protégés and kith and kin". Copts, thus, were allowed to freely practice their religion and were to a large degree autonomous, provided they continued to pay a special tax, called "Gezya", that qualifies them as "Ahl Zemma" protégés (protected). Individuals who cannot afford to pay this tax were faced with the choice of either converting to Islam or losing their civil right to be "protected", which in some instances meant being killed. Copts, despite additional sumptuary laws that were imposed on them in 750-868 A.D. and 905-935 A.D. under the Abbasid Dynasties, prospered and their Church enjoyed one of its most peaceful era. Surviving literature from monastic centers, dating back from the 8th to the 11th century, shows no drastic break in the activities of Coptic craftsmen, such as weavers, leather-binders, painters, and wood-workers. Throughout that period, the Coptic language remained the language of the land, and it was not until the second half of the 11th century that the first bi-lingual Coptic-Arabic liturgical manuscripts started to appear. One of the first complete Arabic texts is the 13th century text by Awlaad El-Assal (children of the Honey Maker), in which the laws, cultural norms and traditions of the Copts at this pivotal time, 500 years after the Islamic conquest of Egypt were detailed. The adoption of the Arabic language as the language used in Egyptians' every-day's life was so slow that even in the 15th century al-Makrizi implied that the Coptic Language was still largely in use. Up to this day, the Coptic Language continues to be the liturgical language of the Church.

The Christian face of Egypt started to change by the beginning of the second millennium A.D., when Copts, in addition to the "Gezya" tax, suffered from specific disabilities, some of which were serious and interfered with their freedom of worship. For example, there were restrictions on repairing old Churches and building new ones, on testifying in court, on public behavior, on adoption, on inheritance, on public religious activities, and on dress codes. Slowly but steadily, by the end of the 12th century, the face of Egypt changed from a predominantly Christian to a predominantly Muslim country and the Coptic community occupied an inferior position and lived in some expectation of Muslim hostility, which periodically flared into violence. It is remarkable that the well-being of Copts was more or less related to the well-being of their rulers. In particular, the Copts suffered most in those periods when Arab dynasties were at their low.

The position of the Copts began to improve early in the 19th century under the stability and tolerance of Muhammad Ali's dynasty. The Coptic community ceased to be regarded by the state as an administrative unit and, by 1855 A.D., the main mark of Copts' inferiority, the "Gezya" tax was lifted, and shortly thereafter Copts started to serve in the Egyptian army. The 1919 A.D. revolution in Egypt, the first grassroots display of Egyptian identity in centuries, stands as a witness to the homogeneity of Egypt's modern society with both its Muslim and Coptic sects. Today, this homogeneity is what keeps the Egyptian society united against the religious intolerance of extremist groups, who occasionally subject the Copts to persecution and terror. Modern day martyrs, like Father Marcos Khalil, serve as reminders of the miracle of Coptic survival.

Despite persecution, the Coptic Church as a religious institution has never been controlled or allowed itself to control the governments in Egypt. This long-held position of the Church concerning the separation between State and Religion stems from the words of the Lord Jesus Christ himself, when he asked his followers to submit to their rulers: "Render therefore to Caesar the things that are Caesar's, and to God the things that are God's." [Mathew 22:21]. The Coptic Church has never forcefully resisted authorities or invaders and was never allied with any powers, for the words of the Lord Jesus Christ are clear: "Put your sword in its place, for all who take the sword will perish by the sword." (Mathew 26:52). The miraculous survival of the Coptic Church till this day and age is a living proof of the validity and wisdom of these teachings.

Today [as of the writing of this document in 1992 A.D.], there are over 9 million Copts (out of a population of some 57 million Egyptians) who pray and share communion in daily masses in thousands of Coptic Churches in Egypt. This is in addition to another 1.2 million emigrant Copts who practice their faith in hundreds of churches in the United States, Canada, Australia, Britain, France, Germany, Austria, Holland, Brazil, and many other countries in Africa and Asia. Inside Egypt Copts live in every province and in no one of these provinces are they a majority. Their cultural, historical, and spiritual treasures are spread all over Egypt, even in its most remote oasis, the Kharga Oasis, deep in the western desert. As individuals, Copts have reached prestigious academic and professional stature all over the world. One such individual is Dr. Boutros Boutros Ghali the Sixth United Nations Secretary-General (1992-1997). Another is Dr. Magdy Yacoub one of the world's most famous heart surgeons.

Copts observe seven canonical sacraments: Baptism, Christmation (Confirmation), Eucharist, Confession (Penance), Orders, Matrimony, and Unction of the sick. Baptism is performed few weeks after birth by immersing the whole body of the newborn into especially consecrated water three times. Confirmation is performed immediately after Baptism. Regular confession with a personal priest, called the father of confession, is necessary to receive the Eucharist. It is customary for a whole family to pick the same priest as a father of confession, thus, making of that priest a family counselor. Of all seven sacraments, only Matrimony cannot be performed during a fasting season. Polygamy is illegal, even if recognized by the civil law of the land. Divorce is not allowed except in the case of adultery, annulment due to bigamy, or other extreme circumstances, which must be reviewed by a special council of Bishops. Divorce can be requested by either husband or wife. Civil divorce is not recognized by the Church. The Coptic Orthodox Church does not have and does not mind any civil law of the land as long as it does not interfere with the Church's sacraments. The Church does not have (and actually refuses to canonize) an official position vis-à-vis some controversial issues (e.g. abortion). While the church has clear teachings about such matters (e.g. abortion interferes with God's will), it is the position of the Church that such matters are better resolved on a case-by-case basis by the father of confession, as opposed to having a blanket canon that makes a sin of such practices.

There are three main Liturgies in the Coptic Church: The Liturgy according to Saint Basil, Bishop of Caesarea; The Liturgy according to Saint Gregory of Nazianzus, Bishop of Constantinople; and The Liturgy according to Saint Cyril I, the 24th Pope of the Coptic Church. The bulk of Saint Cyril's Liturgy is from the one that Saint Mark used (in Greek) in the first century. It was memorized by the Bishops and priests of the church till it was translated into the Coptic Language by Saint Cyril. Today, these three Liturgies, with some added sections (e.g. the intercessions), are still in use; the Liturgy of Saint Basil is the one most commonly used in the Coptic Orthodox Church.

The worship of Saints is expressly forbidden by the Church; however, asking for their intercessions (e.g. Marian Praise) is central in any Coptic service. Any Coptic Church is named after a Patron Saint. Among all Saints, the Virgin Saint Mary (Theotokos) occupies a special place in the heart of all Copts. Her repeated daily appearances in a small Church in Elzaytoun district of Cairo for over a month in April of 1968 was witnessed by thousands of Egyptians, both Copts and Muslims and was even broadcast on International TV. Copts celebrate seven major Holy feasts and seven minor Holy feasts. The major feasts commemorate Annunciation, Christmas, Theophany, Palm Sunday, Easter, Ascension, and the Pentecost. Christmas is celebrated on January 7th. The Coptic Church emphasizes the Resurrection of Christ (Easter) as much as His Advent (Christmas), if not more. Easter is usually on the second Sunday after the first full moon in Spring. The Coptic Calendar of Martyrs is full of other feasts usually commemorating the martyrdom of popular Saints (e.g. Saint Mark, Saint Mina, Saint George, Saint Barbara) from Coptic History.

The Copts have seasons of fasting matched by no other Christian community. Out of the 365 days of the year, Copts fast for over 210 days. During fasting, no animal products (meat, poultry, fish, milk, eggs, butter, etc.) are allowed. Moreover, no food or drink whatsoever may be taken between sunrise and sunset. These strict fasting rules -- which have resulted in a very exquisite Coptic cuisine over the centuries -- are usually relaxed by priests on an individual basis to accommodate for illness or weakness. Lent, known as "the Great Fast", is largely observed by all Copts. It starts with a pre-Lent fast of one week, followed by a 40-day fast commemorating Christ's fasting on the mountain, followed by the Holy week, the most sacred week (called Pascha) of the Coptic Calendar, which climaxes with the Crucifix on Good Friday and ends with the joyous Easter. Other fasting seasons of the Coptic Church include, the Advent (Fast of the Nativity), the Fast of the Apostles, the Fast of the Virgin Saint Mary, and the Fast of Nineveh.

The Coptic Orthodox Church's clergy is headed by the Pope of Alexandria and includes Bishops who oversee the priests ordained in their dioceses. Both the Pope and the Bishops must be monks; they are all members of the Coptic Orthodox Holy Synod (Council), which meets regularly to oversee matters of faith and pastoral care of the Church. The Pope of the Coptic Church, although highly regarded by all Copts, does not enjoy any state of supremacy or infallibility. Today, there are over 60 Coptic Bishops governing dioceses inside Egypt as well as dioceses outside Egypt, such as in Jerusalem, Sudan, Western Africa, France, England, and the United States. The direct pastoral responsibility of Coptic congregations in any of these dioceses falls on Priests, who must be married and must attend the Catechetical School before being ordained.

Read more on [ The Christian Coptic Orthodox Church Of Egypt ]